Chasing Grapes, Shaping Forces, and Crushing Fears

Part II of "Colorado Wines Embody Natural Geography of a Sustainable Economy."

By John H. Giordanengo

Before attempting to restore an economy (to a sustainable state) it is important to embrace its boundary, and the forces naturally existing there. With a fractured bone, a broken-down car, or a leaking roof, we know the structure of the system and its boundary, and we often know the forces causing the damage: gravity, friction, hail, and so forth. With an economy or ecosystem, the boundaries area harder to define, as they’re a bit fuzzier.

These next two articles address the question of scale (the natural geographic boundary) of a sustainable economy. Should our products (wine for instance) and energy flow across global boundaries, or is it more natural (and sustainable) for them to flow across state, regional, or local boundaries?

This article begins with concepts such as resilience, resistance, and the nature of competition and collaboration. It ends by showing how natural systems, and martial arts such as Aikido, do not work to actively destroy the forces they face. They embrace those forces as a natural part of their context, and harmonize with them to do something astonishing. Colorado’s wine industry is a remarkable example.

The Ecological Insight

Resilience is only half of the stability equation

Resilience doesn’t arise from excess comfort. It arises from struggle. That is, the ability to recover after a broken bone, a wildfire, or a fall freeze increases with each new challenge we face. But resilience is only half of the stability equation.* A lot of energy, time, and money is wasted bouncing back after a disturbance—again and again. Ecosystems and economies must also have resistance: the ability to maintain key functions—acquiring, producing, and distributing resources—during a disturbance. This is essential to the system’s survival, and to every entity within.

Disturbances are constant in nature—heavy frosts, drought, small wildfires, and so forth. As casual observers, we rarely notice. The forest and the meadow appear healthy, or even thriving. One factor bolstering resistance and resilience in a forest or meadow, diversity, can also reduce the severity of some disturbances. In Colorado, a ponderosa pine forest that is thinned to a more natural structure (fewer trees, a greater diversity of grass and wildflowers, and so on) is less prone to catastrophic wildfire. When wildfire does strike, most trees remain intact, and the grasses and wildflowers resprout quickly, protecting the soil from erosion.1 The recovery process, succession, was covered in this previous article, along with its implications for peak productivity.

Disturbances (forces) are a natural part of every ecosystem. But disturbance shouldn’t be confused with a shift in the “context” of a forest or grassland. For instance, Colorado endured severe environmental shifts while North America moved from the tropics to its current location over the past 300 million years: several glaciation events; a monstrous asteroid extinguished the dinosaurs and drove 3 of every 4 plant species extinct; and mammals arrived on Earth. Colorado’s ecosystems did not collapse, leaving just dirt and rocks; they adapted. In the process, Earth witnessed the evolution of flowering plants (angiosperms), including the grape vine.

An unlikely partnership

Survival in any environment requires that a species compete more effectively in its niche. Other survival options exist. Should the cheetahs gain a competitive edge over the leopards in hunting gazelles, the leopards may lose their competitive edge. As it stands, leopards hunt primarily at night, and they consume a wider diversity of prey. Cheetahs tend to hunt during the day, and have a narrower diet. The niche, consuming herbivores in the African Savannah, has been partitioned.

Another survival technique is to form a closer relationship with another species—a symbiotic relationship—to acquire resources more efficiently. This includes the European grape, Vitis vinifera, the basis of nearly all wine on Earth. Like all species, native grapes are restricted to the environmental conditions that favor their survival. This is its fundamental niche, the geographic area where a species competes best, and where it forms bonds with pollinators, seed-dispersing birds, microbes in the soil, and so on.

Humans started making wine about 8,000 years ago, and the boundary of Vitis vinifera began to expand. Humans altered the genetics of wine grapes along the way, adapting them to their environmental context and social desires. Wine became more than just a drink for all ages in ancient Mediterranean culture. It was a means to connect the human spirit with the properties of the Earth—a “sign of God’s blessing.”2 Farmers began cutting back competing trees and shrubs, and killing some weeds outright, to favor the most desirable grapes the land would allow.

The Economic Insight

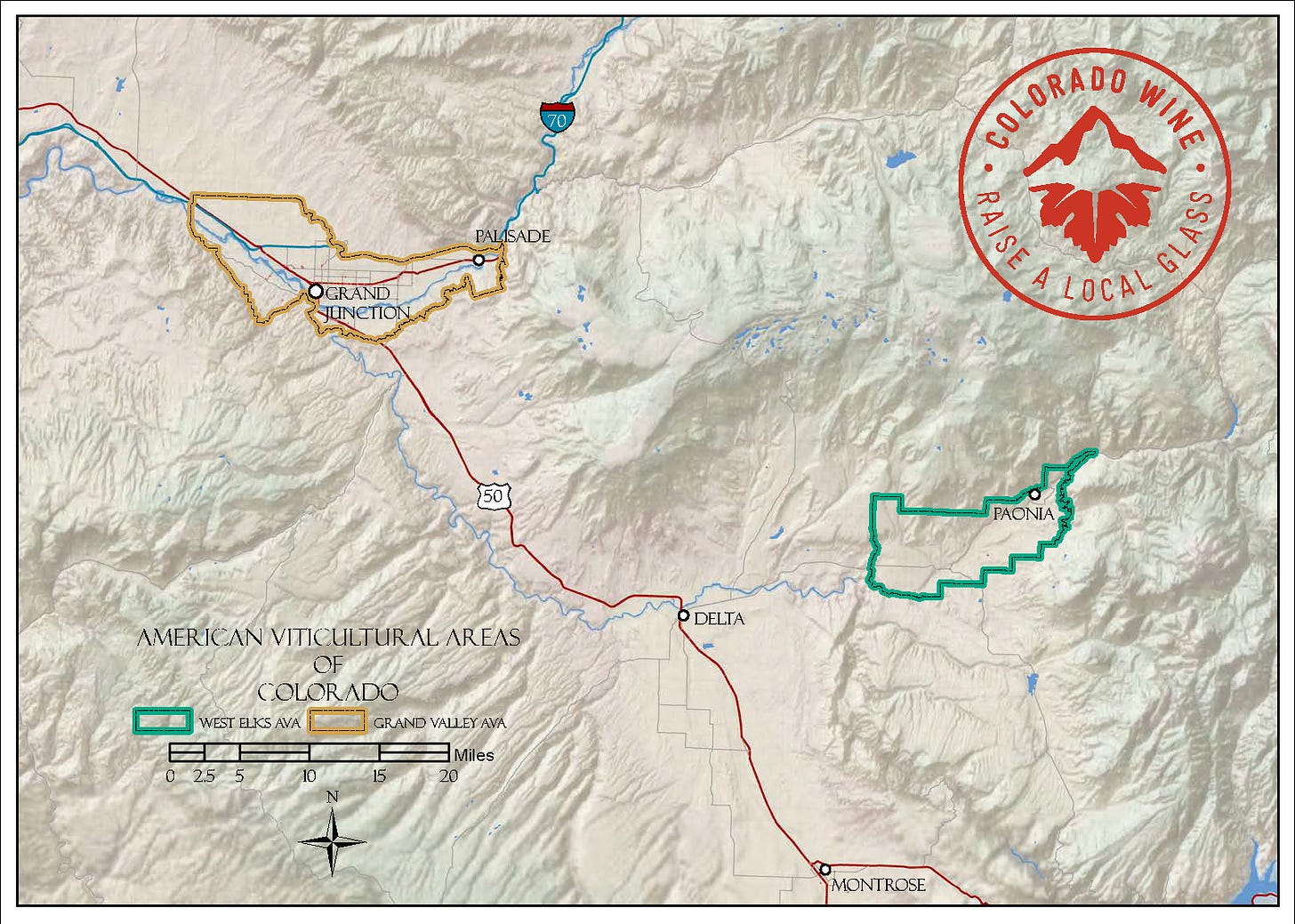

Grape canes (the cuttings from the new year’s growth) were carted across oceans to the new world, and dozens of varieties now flourish in Colorado. A single vine in my backyard produces abundant grapes with very little care. But growing grapes that can be transformed into a sensational wine is entirely different. Just two American Viticulture Areas (AVA) are recognized in Colorado, where the natural geography is most favorable to wine production: the Grand Valley AVA and the West Elks AVA. Travelers from around the world come here to enjoy a greatest diversity of wines.

Map of American Viticultural Areas of Colorado. Map exhibit by the Colorado Wine Industry Development Board.

Crafting competitive advantages

This year’s Uncorked Colorado—an annual event celebrating our best wines—was sensational. Hundreds of Coloradoans gathered to enjoy well-crafted wines and creative foods, surrounded by ancient exhibits in the History Colorado Center. Chatting with winegrowers, winemakers, and wine lovers, I was awe-struck by the struggles, rich history, and creative passion embodied in each glass. As consumers, it’s easy to take it all for granted.

I began by interviewing Kyle Schlachter of the Colorado Wine Industry Development Board (CWIDB), whose team works creatively to strengthen markets for Colorado wines. Kyle was quick to point out that great wine grapes exist not just in Colorado’s AVAs but also around Cortez, and in the Arkansas Valley on the east slope.3 Several environmental factors favor wine there, such as hot summers, and chilly nights during harvest. A critical social factor also exists: people with a deep history in growing fruit.

Great wines require more than the right environmental and social elements. A business must apply every necessary social, environmental, and industrial force to create a competitive advantage. A competitive advantage is gained when a business produces a wine more efficiently—with fewer inputs or less labor—or by making a higher quality wine than what’s possible elsewhere. Consumers reward competitive advantages daily. When a bottle of wine is the right price, and meets their quality expectations, it goes home with them. And they will come back for more.

Shaping wine’s industrial and social forces

Like the Barolo Boys, the successful Colorado winemaker discovers (and applies) the right techniques at every step in the process—from grape to glass. However, possessing the right technology and knowledge (oak barrels, mixing must with juice, and so on) is useless without possessing the right creativity.

Creativity doesn’t always arise where we expect it to. Case in point, the 2024 Colorado Governor’s Cup for best wine was awarded to a business better known for brewing great beers: Odell Brewing Company (OBC) of Fort Collins. The OBC Wine Project was launched during COVID to diversify the brewery’s product line, but the shift was also driven by a supplier. OBC’s hops provider started growing grapes, to diversify their own business.4 During the fall “crush”, I enjoyed some time with OBC’s winemaker, Travis Green. A crush is just what it sounds like: pressing grape juice from its protective skin. Casually, Travis shared that Colorado growers are producing the same high quality grapes as those in Oregon or Washington.5

Fresh juice and grape must (skins and seeds) at OBC Wine Project in Fort Collins, CO. Photo by John H. Giordanengo, Economic Restoration Services.

Travis’s award-winning Colorado Red is a blend of Grand Valley grapes. One of them is Teroldego, a varietal from the foothills of the Dolomites in NW Italy. Colorado Red includes two other varietals I’d never heard of: Chambourcin, a French-American hybrid that is cold hardy and medium-bodied; and Cabernet Franc (Cab Franc), a complex black grape from Southern France.

A day in the life of Travis can include chasing down the best grapes in Colorado, crushing them just the right way, aging them in the right barrel, and bottling them under the right name. Every step is essential. What’s the right time to harvest this specific grape? How long should the must (skin, seeds, and stems) mix with the juice? What barrel should this vintage be aged in, and for how long? Should wine only exist in bottles?

Adapting wine to Colorado’s beer-drinking crowd, Colorado Red also comes in 12 oz cans: light proof, highly recyclable, and more energy-efficient than glass bottles.

Center: Travis Green of OBC Wine Project receives Governor’s Cup award at Uncorked Colorado on Nov 1, 2024. Right: Kyle Schlachter of CWIDB. Left: Libby Geboy of CWIDB. Photo courtesy of the Colorado Wine Industry Development Board.

The Promise of Diversity

One of nature’s most obvious lessons for every business, industry and economy is to diversify. Ecologists quantify diversity by counting the number of species, such as the 58 plant species in my backyard. Economists measure diversity by counting the number of businesses. The diversity of Colorado’s wine industry—more than 150 wineries—is essential to its success. And a thriving wine industry can support each wine business within.

For Sauvage Spectrum, a Grand Valley estate producing Teroldego grapes, diversity means growing dozens of grape varieties. Their Teroldego received a gold medal in 2023, but they grow another variety I’d never heard of until chatting with Sauvage Spectrum’s winemaker, Patric Matysiewski. It’s a century-old red hybrid from Austria called Zweigelt.6 If you’re skeptical of hybrid wines, know that Cabernet Sauvignon is a hybrid between Cabernet Franc and Sauvignon Blanc. Listening to Patric describe the Zweigelt he’s aging right now, it is possible this varietal will change our concept of Colorado wines. It will hit the streets in 2025 under the solitary name Zweigelt.

The great freeze (again)

Colorado’s wine industry was tested ruthlessly in the fall of 2020 when a horrific October freeze struck the Grand Valley. Trunks split wide open, buds burst, and cane cells erupted. Vine canes are essential to next season’s growth.

“We had to cut them off at the ground and re-tie new canes onto the wire the following season. In addition to an immense amount of labor we lost a whole year of production.” ~ Kaibab Sauvage

Sauvage Spectrum’s wine grower, Kaibab Sauvage, recalled that “…all of our cold hardy varieties came through the freeze relatively unharmed: Aromella, Chambourcin, Vignoles, and others. These were planted as safety nets after our devastating 2014 frost that wiped out nearly 90% of our vines.”7 Diversity is essential for another reason; so that Patric, Travis, and others have a full spectrum of flavors to create with.

The wild one

Sauvage takes diversity further, by growing a wide variety of fruits with the same land. “We need a diverse selection of fruit for the entire season (color on the table, as they say at the market).” Six varieties of apricots, 20 varieties of peaches, 12 varieties of plums, as well as prunes, apriums, and nectarines. Three varieties of apples on 75-year-old trees. Certainly, I’ve left something out. The French word sauvage translates to “wild,” so I would expect nothing less from this estate than grand diversity.

The most enduring business is not the one that amasses the most possible revenue in a single year, but the one whose strategy yields adequate revenue year after year. Since no two years are the same, diversity is that essential strategy. Diversity also provides something to harvest from June to September—more continual work for Kaibab’s crew. There are days in early September when the crew pick peaches, pears, plums, and grapes all on the same day.

The team at Sauvage Spectrum, Grand Valley, CO. Photo courtesy of Sauvage Spectrum Estate Winery & Vineyard.

An odd diversity challenge

Patric raised an odd challenge for Colorado wines, a phenomenon unheard of in the natural world. About 90% of the world’s wine market is dominated by five varietals. Among them is Cabernet Sauvignon. I admit, it’s the red wine I typically reach for on the shelf. The other four are Merlot, Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc and Pinot Noir. “Nobody knows Teroldego,” Patric bemoaned. Nor do they know Chambourcin, Petit Verdot, and dozens of others thriving here. The collective consumer palate lacks diversity.** It’s not as “evolved” as Colorado’s beer palate.

Can the spirit of the Earth be bottled?

A friend referred me to his Aikido instructor, who started Tamburi, a Fort Collins winery that crafts Merlot and Cabernet Franc wines using all natural techniques. For perspective, Tamburi has never attended an Uncorked Colorado event. For more perspective Tamburi’s winemaker, Altin Papa, never uses sulfites or artificial yeasts. Altin does age his wines in oak barrels that are on their fourth (or so) life—barrels that once held whiskey, beer, and other wine vintages. “The barrel is just a convenient sealed container,” Altin reminded me. He doesn’t rely on oak tannins for flavor. Altin wants his wines to reflect the pure essence of the grapes.

Merlot and Cab France aging in barrels at Tamburi Winery, Fort Collins. Photo by John H. Giordanengo, Economic Restoration Services.

It is fateful, perhaps, that native grapes have a symbiotic relationship with local yeasts: the white bloom sticking to the grapes’ waxy skins. Yeasts are floating around in the air everywhere, and are essential to the fermentation process. Tamburi wines reflect not simply the terroir of the Grand Valley, and its yeasts, but the yeasts and various other elements in the northwest corner of Fort Collins.

Altin and I enjoyed deep conversations while sniffing, swirling, sipping, and staring into each wine glass. I was completely ignorant of Cab Franc, and I’d never tasted a Colorado Merlot. In truth, my expectations were low. In fact, however, the Merlot was mesmerizing. But words are a poor reflection of our emotions, Altin and I agreed. All I know is that I’ll be going back to the Farmer’s Market soon, and I’ll be carting more Tamburi bottles back home.

As for the Cab Franc, a collage of tones rose up from the glass that I didn’t know existed. As a musician, my first thought was avant-garde Jazz, another inadequate description. I was transported to a place I’d never been. I had to admit to Altin, “I’m afraid to take a sip,” for fear that my tastebuds would not live up to the experience my nose just had. I sipped, of course, and am now a Cab Frank lover for life. And I accept that Cab Franc will not be the same anywhere else on earth. “The grapes did good things last year,” Altin acknowledged.

Discovering a New Colorado Wine

This holiday season, share the gift of a true Colorado experience with your family and friends. While out shopping for something under the tree, grab some Colorado wine for the table. Most CO liquor stores carry Colorado wines, but I’ve found the greatest selection at Supermarket Liquors, a family-owned business in in Fort Collins. If your favorite store or restaurant doesn’t carry Colorado wines, demand them. Demand is a key driver of supply.

For a truly memorable experience, walk into the OBC Wine Project or the Tamburi Winery tasting room in Fort Collins; or head over to Sauvage Spectrum, CarBoy Winery, or dozens of others in the Grand Valley. Smell, sip, and connect with the roots of this remarkable Earth we call home.

A map of Colorado wineries is available on the CWIDB website.

If you desire a deeper melding of ecology and economics, feel free to reserve a copy of Ecosystems as Models for Restoring our Economies (To a Sustainable State), 2nd edition scheduled for release in March 2025 by Anthem Press.

* In ecology and economics, stability is a factor of resilience and resistance to disturbance. However, stability is a relative term, and disturbances come in a variety of types, intensities, and frequencies.

** Incidentally, the word palate (the roof of the mouth) may have derived from the Etruscans,8 a primitive Italian society. The Etruscans predated the Romans, and were among the first Italians to adopt winemaking from the Greeks—nearly 3,000 years ago. Etruscan winemaking was so successful it began to be shipped across the Mediterranean. The Etruscans have historically occupied the Trentino region, where the great Teroldego grape varietal was born.

Literature Cited

Miller et al. 2017. Learn from the Burn: The High Park Fire 5 Years Later. USDA, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Science you can use bulletin. May/June 2017. Issue 25. https://research.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/54288

Fuller, R. 2014. ‘Let us adore and drink!’ A brief history of wine and religion. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/let-us-adore-and-drink-a-brief-history-of-wine-and-religion-35308#:~:text=In%20ancient%20Mediterranean%20culture%2C%20wine,%2C%20Amos%209:24)

Schlachter, K. 2024. (Executive Director of the Colorado Wine Industry Development Board). Phone interview by John Giordanengo, 28 Oct 2024.

Baise, K. 2024. (Community Outreach Coordinator, Odell Brewing Company). Interviewed in person by John Giordanengo, Fort Collins, Colorado, 08 Dec, 2024.

Green, T. 2024. (Winemaker, OBC Wine Project). Interviewed in person by John Giordanengo, Fort Collins, Colorado, 17 Nov., 2024.

Matysiewski, P. 2024. (Winemaker, Sauvage Spectrum Estate Winery and Vineyard). Interviewed over phone by John Giordanengo, 18 Nov., 2024.

Sauvage, K. 2024. (Winegrower, Sauvage Spectrum Estate Winery and Vineyard). Interviewed over phone by John Giordanengo, 18 Nov., 2024.

Etymology Online Dictionary. 2024. “Palatine.” Accessed 8 December, 2024. https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=palatine